The vision I saw was basically this: men and women alike are called to the same three offices; that of priest (to offer sacrifice), that of king (to lead and to fight), and that of prophet (to bring forth a word of insight). What differs between the genders is that the primary calling among these three offices for women is the prophetic office, while for men, it is the kingly office.

~Timothy Patitsas

In an interview with Paris Review in 1960, Robert Frost recalled his first meeting with Ezra Pound in London.

After calling on Pound at his London residence, Frost admitted under interrogation that he’d yet to receive a copy of his debut book of poems, A Boy’s Will. Pound insisted they walk to the publisher immediately and get it. Pound, not Frost, got his hands on the book first and put it in his pocket. Returning to his flat, and after a few minutes of watching his compatriot read his book, Pound said “you better run along home. I’m going to review it.”

“And I never touched it,” said Frost. “I went home without my book and he kept it. I’d barely seen it in his hands…That’s one of the best things you can say about Pound: he wanted to be the first to jump.”

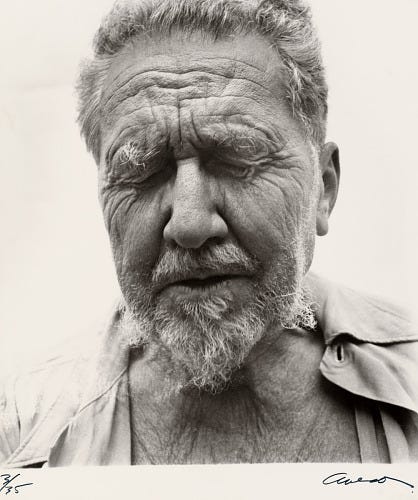

The exact truth of this recounting is immaterial; Ezra Pound was instrumental in launching the careers of many writers we now consider great. The list, Frost included, was comprised of such writers as T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, William Carlos Williams, and James Joyce, among others. Ezra, this single child from rural Idaho, grew up to become the most dynamic literary figure of English language poetry in the 20th century, furiously writing letters, bossing dinner parties, and insulting prominent figures across Europe and North America.

After establishing himself abroad, Pound introduced himself to the unsuccessful writer James Joyce through their mutual friend W.B. Yeats. Joyce wrote to his compatriot shortly after: "I can never thank you enough for having brought me into relation with your friend Ezra Pound who is indeed a miracle worker."

Ezra Pound was not a great poet, or critic for that matter. He was, however, a talented editor, and an exceptional literary figure. He connected the world of poets and writers to the world of publication and funding in a way that no one else was capable of. Few poets have inhabited the role of the modern poet so well, so obnoxiously, with such fervor, for so long.

The same force with which he bolstered his persona was applied to his 800 page “masterpiece”, The Cantos.

Canto CXVI

I have brought the great ball of crystal;

Who can lift it?

Can you enter the great acorn of light?

But the beauty is not the madness

Tho' my errors and wrecks lie about me.

And I am not a demigod,[q]

I cannot make it cohere.

After reading the whole thing as a young man, I spent a good year writing poems in this ridiculous style. Although the work has its merits, I likely could have found something more productive to do…but madness of the effort was inspiring.

Pound, from the beginning, was a true believer. In what precisely he believed, it is hard to say. As WWII began he decided the world was going to hell, which it was, and acted accordingly with what resources he had: primarily his relentless spirit. It was only after being tried for treason for his pro-fascist broadcasts during the war that he changed gears. The man spent 13 years at St. Elizabeth Psychiatric Hospital in Washington, D.C., the majority of which was spent in silence.

Pound was not a man of great genius or virtue, but of enthusiasm. He led the way, for better and for ill, annoying and inspiring those in his wake. The poetry world is irrelevant for the lack of such characters.

But the great king not only leads but lays down his life as a sacrifice for his people. Did Pound do this? The question is really asked of us.

Canto LXXXI

What thou lovest well remains,

the rest is dross

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee

What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage

Whose world, or mine or theirs

or is it of none?

First came the seen, then thus the palpable

Elysium, though it were in the halls of hell,

What thou lovest well is thy true heritage

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee