Strong were our Syres; and as they Fought they Writ, Conqu’ring with force of Arms, and dint of Wit; Theirs was the Gyant Race, before the Flood; And thus, when Charles Return’d, our Empire stood. … Our Age was cultivated thus at length; But what we gain’d in skill we lost in strength. Our Builders were, with want of Genius, curst; The Second Temple was not like the First. John Dryden, "To Mr. Congreve" (1694)

Towards the end of his life, Goethe reflected that “a productive nature ought not to read more than one of Shakespeare’s dramas in a year if he would not be wrecked entirely.”

Speaking with his friend Johann Peter Eckermann, Goethe continued:

…to study him is to become aware that Shakespeare has already exhausted the whole of human nature in all directions and in all depths and heights, and that for those who come after him, there remains nothing more to do…had I been an Englishman, and had those manifold masterworks pressed in upon me with all their power from my first youthful awakening, it would have overwhelmed me, and I would not have known what I wanted to do! I would never have been able to advance with so light and cheerful a spirit, but would certainly have been obliged to consider for a long time and look about me in order to find some new expedient.”

It’s quite depressing, really, coming from the Übermensch himself.

In Walter Jackson Bate’s first lecture, he begins with the question that has thrust itself with progressively greater force upon the poet and artist for the past three centuries: what is there left to do?

One can hardly argue that since the Renaissance, the means of producing and distributing literature has increased dramatically, leaving the artist confronted with an increasingly varied and voluminous array of artistic achievements. The 18th-century English-speaking poet also had the unenviable task of wrestling with immediate predecessors such as Donne, Johnson, and Milton.

The disruption and dissolution of religious faith, the entrance of mass media, a bloated and inert academia, the increasing complexity of everyday life, and other factors have undoubtedly contributed to what many perceive as the decline of the arts, but Bate posits that these are all peripheral to the central problem: the lack of self-confidence of the artist when faced with the sweeping grandeur of past achievements. He notes that this “remorseless deepening of self-consciousness” and general despondency has not plagued scientists and the non-creative man of the humanities.

Here Bate brings in Thomas De Quincy’s helpful distinction between the “literature of knowledge” and the “literature of power.” Critics, biographers, and historians dealing with facts and expository details can content themselves with discovering a new and disruptive set of facts here or supplementing or debating an argument there. Still, even the most astute scholar’s work is provisional. Their work “can always be superseded. But the Iliad or King Lear will not be dislodged with the same ease or excuse. They are, as De Quincy said, “finished and unalterable—like every other work of art, however minor.”

Bate turns his attention to the milieu of the 18th-century poet because “it is the first period in modern history to face the problem of what it means to come immediately after a great creative achievement.”

This involves the examination of English neo-classicsm. And we are not dealing primarily with neo-classic theory but the far messier business of the reciprocal influence of neo-classical ideas and art. In our present moment, it is fashionable to obsess over the history of critical theories, tracing genealogies of thought with a Sherlockesque glee while largely ignoring that this is not one-way traffic, with ideas influencing artists and never the other way around. (In fifty years, it will be fascinating to read the literature surrounding the impact that The Matrix, created by the Wachowski brothers/sisters, had on gnostic thought in the early 21st century.)

The central neo-classic concept is decorum, where the relevance or fitness of every part is examined in light of the whole. “Its origin was the ancient Greek and specifically Aristotelian conception of the function of art as a unified, harmonious imitation of an ordered nature.” This sophisticated “almost monolithically systematized” French import was too hard to resist for the English. It allowed the poet to be different than his immediate forebears and gave him a further support: any objections could be answered with an appeal to reason. And “to dismiss an argument that led directly back to “reason” was something they were not prepared to do. It was like attacking virtue itself.”

Taken onboard almost entirely wholesale, this framework of formal decorum would last for many profitable years. Bate:

“Never before in the West since classical antiquity…has there been available for the poet or artist generally and also for the critic or philosopher, or for anyone who wanted to say anything about the arts, a concept that could potentially fulfill so many functions. It not only could serve as an active hinge between the theory of art and the actual practice of it, but could lead directly to moral and social values, and further, to nature itself and the cosmic order.”

This happy new arrangement also allowed the critic and poet to invoke an authority from a more distant (and thus “purer”) past. It was “not an authority looming over you but, as something ancestral rather than parental.” The poet could breathe. We see T.S. Eliot taking a page out of this playbook, citing the historically more distant metaphysical poets as part of the genuine English tradition while bashing the more recent “adolescent” Romantic Shelley.

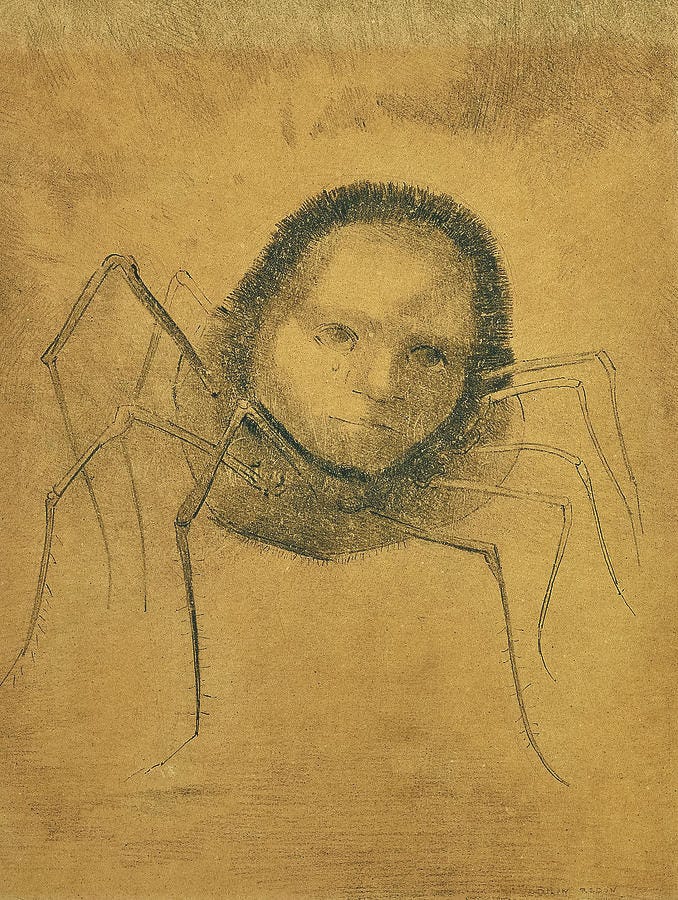

Predictably, hysterically, inevitably, and ever so humanly, the Ancients were critiqued for not being sufficiently classical. Sorry, Homer, but you’re just not “correct” enough; there’s just too much flotsam in this story. In Jonathan Swift’s The Battle of The Books, he uses the bee as the symbol of the Ancients and the spider of the Moderns.

Bate again:

“The bee, turning directly to what is outside of us (nature), brings home honey and wax, thus furnishing man with both “sweetness and light.” The spider, by contrast, is a domestic creature, working within a shorter radius, indeed preferring a corner. The tireless weaving of rule and regulation that Swift is attacking in the Moderns, far from being the product of a direct and far-ranging use of “nature,” is spun subjectively from the spider’s own body, and the web—at once systematic and flimsy—is capable only of catching dirt and insects.”

Ben Johnson was right in saying that “it is more easy to take away superfluities than to supply defects,” or, that is, to forbid rather than to incorporate. I don't wish to give the impression that Bate or myself are tut-tutting our 18th-century friends here. Their approach was sane, measured, and productive.

As Dryden acknowledged in his Essay of Dramatic Poesy regarding Shakespeare and the writers of his age, the turn to other modes of writing was far more a tribute to their greatness than a reproof. He writes that he and his contemporaries “acknowledge them our fathers,” and that their choice is “either not to write at all, or to attempt some other way.”

In Dryden's poem written to his friend William Congreve that began this essay, he describes these writers as a “giant race before the flood” —before the seismic change in form and content that switched its focus towards what seemed to be the formal essentials found in the classical achievement. In the poem he goes on to write:

Our Age was cultivated thus at length; But what we gain’d in skill we lost in strength. Our Builders were, with want of Genius, curst; The Second Temple was not like the First.

Bates then concludes his first lecture by saying:

The Second Temple, completed seventy years after the destruction of the First by Nebuchadnezzar, differed in four ways especially from the Temple of Solomon. Though about the same in area, it was not so high. It was also less of a unit, being divided now into an outer and inner court. In equipment and decoration it was barer. Above all, the Holy of Holies was now an empty shrine, as it was also to remain in the magnificent Third Temple built by Herod. The Ark of the Covenant was gone, and no one felt at liberty to try to replace it with a substitute.

We will pick up next week with Bate’s second lecture in The Burden of The Past and The English Poet, titled “The Neoclassic Dilemma.”

If there's still time left, that could only be because there are still saints left. And if there are still saints left, there's need for poets to write about them.

Plus, the Second Temple always gets denigrated because the cloud of glory never descended on it like it did in Solomon's time. But behold, One greater than Solomon entered the Second Temple in the flesh, and did so regularly.