I.

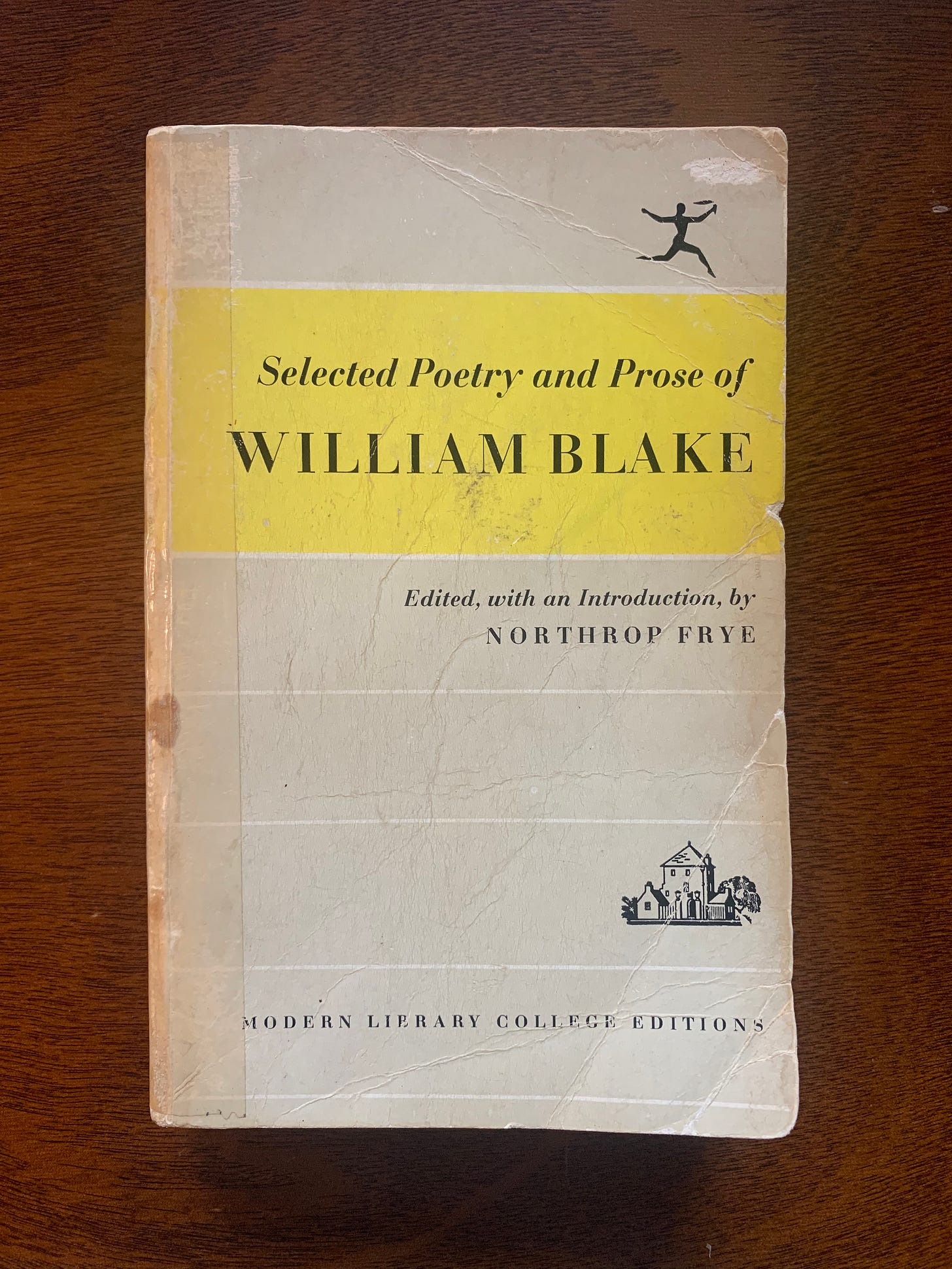

The text pictured below I found in a bookstore in Northern California. I was a moderately literate fifteen year old, though I spent most of my time engaged in whatever all the other fifteen year olds were doing. Generally, it was not a high manner of living. Aside from martial arts and collegiate wrestling, my time was used in Whiterun and Rick and Morty’s garage; on my better days, I listened to Joe Rogan expostulate against both sense and sensibility. I look back on it now as a time of profound grace, for which cause I will do as the psalmist says, and bless the Lord as long as I have my being.

I am going to depart from my usual style of address in the forthcoming, as befits, I think, my subject.

The lamprey nihility of the dopaminergic chain-gang to which the secular American teenager is bound by an ontological blood-pact had left me eviscerated. Not only could I not digest the strong meat of the Truth, but milk became literally too much for me (this seems among my kin in kronos something of a regularity, as our flesh becomes prolific in deficiencies of gastronomic aptitudes). Also, we don’t treat our cows very well, which I imagine contributes.

This is hard write. Almost a public confession. Hopefully it’s helpful, and not somehow disenchanting. My point is doxological, when it comes to it. I can only make it with the hope that you, wise reader, will receive my poems hereafter in a spirit of human confraternity, buying the field in hopes of the pearl. After all, I only contribute the dough, not the leaven.

There was a book-shop that I had frequented in search of Brian Jacques, Robert Jordan, and Arthurian lore in childhood (all the cool people I know read Jacques as a kid). I have no idea how long it has been there, but I do know its origin story; suffice to say, it involves gold-mining, talking worms, and the Golden Dawn. It is a gem of a place. Anyways, for whatever reason, I was there, and betook myself to the Poetry section. For the size of this bookstore (Cal’s Books, in Northern California stop by if you’re on the road) the poetry section is rather small. This is often the case. I have since been to this particular bookstore probably a hundred times; the same poetry titles are generally still there. I often leave my favorite volumes on the shelf, unpurchased, thinking of The Providential Reader.

That little Modern Library Edition made itself noticeable to me, like a star flirting with sublunar hearts, and I bought it.

Now that I am somewhat of a self-ennobled aristocrat, I almost wonder how Blake’s verse has made it through the ringer of ‘bald heads with ink on their shoes’, to end up in critical editions and the like. His language is frenetic, offensively obtuse, and altogether too simple realize the weight of its prophetic verisimilitudes. His poems are at once childlike and oracular. Innocence and Experience.

Tyger! Tyger!

There is something about William Blake’s verse that seems capable perforce of corroding one’s worldview while simultaneously bestowing upon one’s head a blessing of (it may be infernal) fire. I won’t talk about what that is right now, but he seems to figure into a lot of these stories. Maybe we’ll start collecting them.

For myself, it was his joy, I think, that caught me. His verse is lyric and metaphysical. His images are of children and lambs and angels and engines of strange fire. He was, by virtue of the strength and oddness of his verses alone, an artifact of a world in which I had not yet stepped foot, and that, importantly, was possible to inhabit. The fact that he was, or had been, gave sinews (another Blakean word) to Shakespeare’s “There are more things in Heaven and Earth… than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

II.

The Providential Reader, who is he? Why, he or she is you.

Charles Taylor talks about the Ethics of Authenticity. Deconstructionist epistemologies of uncertainty are secretly motivated by the unconscious legerdemain of souls who deeply long for beauty and honour, but find themselves rather like sons of a great inheritance, who have spent their lives feeding upon fungal pods among crimson swine. We are ashamed.

According to our prototype (but not, thanks be, our archetype) we tend to attempt the amelioration of this shame by 1. blaming every one of the ‘ten thousand things,’ and God their source, or 2. making habiliments of fig leaves, and pitying ourselves.

I was born in 2002. Continuing to read beyond this point, proves that you, venerable pursuer of Silver Door, are inhabited by a profound humble-mindedness. Neither I nor my generation have earned the right to speak. Only Christ was of such a kind as to stand up among the elders and teach. Luckily, this piece is less about teaching, than about showing. Nevertheless, I prefer to take a roundabout approach, and so this essay will touch on probably fifty things. They say of my generation as well, that we have trouble focusing.

I am in favour of a soft obliteration of cultural self-identification as artist. It is a word too often slurred through sherbert and sepia and strange Baroque grotesques, beige sharp-cornered things and images of enforced narcissistic aloneness. Telescopes and towers, while true enough images of the perceptive eye, seem over-likely in our day and age to catalyze an art of inscrutable self-reference. We are crafts-people, and cannot claim the badge of the guild, for none of us had any masters.

Through William Blake, I fell in love with the Romantics. Here was the possibility of a pure aesthetic, a pure poeisis. A fluid metaphysics of beauty and the beauteous. Thomas Chatterton, the patron saint of Romanticism, can tell you briefly and instructively of the movement’s flaws.

Alas, “fancy cannot cheat so well/ as she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.”

And though the Romantics were able to give me, as it were, a shot of spiritual adrenaline, my world was nevertheless a world of Blockbusters and Walmarts and Spotify and Chicken-fingers and Transformers and Drake and, worst of all, other people.

These last seemed especially adept at hammer-fisting the glass dome of the imaginal Hagia Sophia that I had laboured so long and aerily to construct.

“...to make the mind ‘go out’ not only from fleshly thoughts, but out of the body itself, with the aim of contemplating intelligible visions—that is the greatest of the Hellenic errors, the root and source of all heresies, an invention of demons, a doctrine which engenders fully and is itself the product of madness. As for us, we recollect the mind not only within the body and heart, but also within itself.”

-St. Gregory Palamas

Boy, did I do that. My pretensions of genius should have worn leper-bells.

I lived and live a somewhat normal American life. I have seen countless hours of tv, eaten the microwavable black plastics associated therewith, snap-chatted and memed. My neighbors want me to join a D&D campaign with them, which offends superlatively my ideals of almost eremitic artist-ness and the sacerdotal aloofness of the gnostic poet. There are good forms of renunciation, certainly, but there is also the pride of the bourgeois which causes one to abstain from the hale traditions of the folk.

It is very troublesome, when one is preening his feathers, to be reminded of this actualness. An actualness in which the everywhere-present God is formidably anchored.

Every writer feels like a fake; at least, every writer that has a Vergil.

I have come to believe that this is good. We do suck. Thank God, it’s not about us.

Being a poet has nothing to do with being perfect, and everything to do with repentance. It has nothing to do with you, and everything to do with the Beautiful.

And, as one holy elder puts it, the repentant soul moves like a snail: both slowly, and with its whole house.

Poetry should be an ecstasis on the part of our nature, through our physis, and not from our nature. Our φύσις is given to us by God, and saved by Him. We have to accept our weakness; for it is in weakness that the strength of God is made perfect.

George Steiner says, who are we? what is the people that could put together the words ‘dirty’ and ‘hope,’ as one French poet has done?

We are not disgusted by the opium-habit of Coleridge, or the perversities of Swinburne, as much as we are by our own habits of binge-eating and masturbation. Our penitence is masochistic; we have condemned ourselves to resignation.

The poems I write are an assurance (the good ones, at least) of the Resurrection. Or so it seems to me. If God can wring beauty out of this rag, use the suburban mundanity that so much constitutes my life as brick and mortar of a song, then I need hardly stretch to see Lazarus rising. In the muddy waters of mutability, the eternal lotus blooms.

When I sit down to write, I am offering the substance of my life to God, and asking Him not to waste the chaff of my foolishness. He has the Midas touch.

III.

We are confined to an imminent, punctualist, frame. We decollate our heroes like a hedge-trimmer conforming a druid shrubbery to a neat pollockesque cube of once-verdant leaves: it is possible to make a living plant look like plastic. George Washington had wooden teeth! He had dysentery, one time; he probably also had private financial reasons for committing treason against the crown. Therefore everything he ever did should be, if possible, excised out of the deep mythic strata of your consciousness and hermetically sealed in some sort of lead apotropaic box, and cast into the shale-black fathomlessness of Lethe’s recursive pools.

This essay defeats itself (it definitely repeats itself), in some points, because I am simultaneously trying to distance the centrality of the artist from the Beauty which inspires him or her, and to reify the importance of a humble, ascetical attitude on the part of the artist towards that Beauty, and the inevitably synergetic relationship between the pursuer and pursued: a chiasmic relationship, ultimately, because it is beauty that first of all pursues us.

The hyper-nominalist leveling mentioned above has led writers and poets away from the dialogical possibilities of language, into a landscape of ‘dictated otherness,’ wherein the smallest details of all sensible, psychic and spiritual occurrences has to be painstakingly described, lest the reader should contaminate the narcissistic crystallization of memory on the part of the writer. My prolixity in this essay achieves this in part. I love Richard Wilbur, but he has a poem wherein he describes, very effectively I might add, the way that dust looks under a floorboard. Last year, I listened to Paul Muldoon recite a poem about the history of hardtack. While this tendency is mostly flaccid, it can encourage one to see that the high meanings of our cherished stories and poems are not subject to an ultimate vertical dualism. Consider this poem:

I syng of a mayden That is makeles, king of alle kinges to here sone che chees. He cam also stille Ther his moder was As dew in Aprylle, That fallyt on the gras. He cam also stille To his modres bowr As dew in Aprylle, That falleth on the flowr. He cam also stille Ther his moder lay As dew in Aprylle, That falleth on the spray. Moder & mayden Was nevere noon but she: Well may swich a lady Godes moder be.

These verses are comfortable with the reader or singer. They allow her to inhabit them: to bring to bear her own memories of her mother, of April, of the dew upon flowers; her memories of prayer towards the Mother of God and her Holy Son. For more on this, Jorge Luis Borges gave a germane series of lectures.

It has also led us into a world, where, to justify the functionally prophetical electedness which one has to defend in our culture, if one proclaims oneself Artist (it is like making a claim to the office of shaman), it becomes necessary to find a way to hitch up the quanta of the mundane which do not seem to belong among the ornaments of such distinction. The artist has fits, throws, abnormalities, unexplained and pregnant depressions, sartorial badges of uniqueness, and a plurality of other marks which set him apart as capable of bearing the sacred torch. He is expected to be capable of aesthetically fortifying each and every part of his life. He should be able to write a charming poem about defecation or roadkill. In a way, this is a warped parallel of sainthood: for in the life of a saint, everything does truly become saturated with light, and every choice becomes inextricably bound to the ultimate criterium of perfect and perfective Love.

Once, the artist was expected to repent when confronted with the Beautiful. Today, the artist is expected to repent when confronted with the image of the artist.

He mocked the singer for his theme; Base-born how could that singer sing Of tragical Ilium and Spartan’s queen? Was he so ignorant he did not know Only a virgin’s hand can tame The proud and irascible unicorn? He took the mockery and blessed the shame; It made him see the beauty of his theme That much clearer.

IV.

St. Athanasius’ Life of St. Anthony, 4chan, Flaubert, the essays of Sir Thomas Browne and Charles Lamb, Taco Bell, The Mahabharata, Fidget Spinners, The Book of Job: this is not Everything Everywhere All at Once; it is the inexplicable gifting of reality; this is the Divine Names.

The graffiti of our internal lives is the under-sketching of eight-dimensional noetic Sistine Chapels that angel-draftsmen are ceaselessly at work upon.

George Washington was a hero. He remains one of my heroes. Coleridge was an inspired and godly man. Swinbure a true lover. Rick and Morty is a show that has, I think, deeply consoled hearts thoroughly embittered by the turbulent waters of cynicism; it is a true thing, after its manner. Paul Muldoon’s poem about hardtack was really very good, and hardtack is pretty interesting. The point is, that one could talk about manna in the desert, and also be talking about hardtack, and also be talking about a thousand other more important things. Richard Wilbur’s poem has subtly influenced my perceptions of vagrant dust particles, so that I now imagine them far more glisteringly as golden worlds of faerie-like impermanence. Fidget-spinners reinforce and reveal our psychosomatic togetherness: they prove the reality of the Incarnation. Taco Bell is a fractal image of the Divine Banquet: it serves us when we are hungriest, when we are loneliest. The Lord does not ask us if we are high, or if we are out past legal curfew of our (totally free) State. He gives, and continues to give though we are ungrateful. Taco Bell workers will answer for the most part better than me, when Christ asks them: did you give food to the hungry, drink to the thirsty?

4chan… well, I don’t really know anything about 4chan. I know there’s some good poetry on there; people have sent it to me.

What else can I defend? Skyrim has awoken the first glimmers of the true Voice in many an exiled prince. Joe Rogan wouldn’t sell a lame horse to the village fool. D&D embodies some of the deepest tropes of human life, and if it can be a times kitsch, it is only because we do not take seriously enough the needs that it fulfills. I love Thomas Chatterton. For his sake alone, would be good cause to write beautiful poems. How could any writer not consider him a brother? Romanticism provided, when nothing else had, a plausible architecture of the soul. Whatever its failures, it can open its arms to the Proto-Techton, who can refashion it into an instrument of angelic sensitivity- Tarkovsky’s bell was cast by the prayers of artists and peasants. Of the two men I will mention shortly, Nabokov would have been a saint, had his eros been caught up into the arms of the great super-celestial Master of the Dance. David Foster Wallace was a compassionate soul. He could have written psalms. He could have watered his bed with tears.

My neighbor is my brother, and my brother is my life.

Am I ashamed? Yes: but not of those things which Providence sent me, to spoon-feed me the flame divine, whilst I struggled to begin the Quest which lies before us all.

I am ashamed of all the times that I failed to thank God for all that is, for all that was, for all that will be. For every time that I accepted as my due by grant of some unfathomable claim the being which I have on loan to me, the insurmountable surplus of exquisite beauty which forms the never-to-be-done-away-with seraphic integuments of the Resurrected Life.

V.

By no means do I intend to exonerate any of us from the shame I mentioned earlier. There is a healthy shame (here, I plug Dr. Timothy Patitsas’ The Ethics of Beauty, as conscience requires). I would however, like to liberate us from those paradigms of the fantasy which purport that no prophet could come from Galilee.

Accepting the condition of our life in this world does not mean that one is necessarily subject to meta-conscious etch-a-sketching or to cynical vulgarity. It means to relinquish hope in ourselves, and allow God to sing through us; to make the forests dance and the mountains clap their hands.

The father of English poetry is the shepherd Caedmon. He was a Providential Reader, of sorts. Illiterate, an untalented singer, he would refuse the harp when it was passed in the mead hall. One night, particularly dejected, he left the company of his friends and slept in the shed with the animals under his care. Of a sudden while he slept, and angel appeared to him, and bid him sing of the principium creaturarum- the beginning of created things. Thereafter, Caedmon was blessed with a talent of composition and psalmody unparalleled by his contemporaries. The poem that he sang according to the angel’s command, the first recorded English poem, remains with us. Here it is:

Now let us praise Heaven-Kingdom's guardian, the Maker's might and his mind's thoughts, the work of the glory-father—of every wonder, eternal Lord. He established a beginning. He first shaped for men's sons Heaven as a roof, the holy Creator; then middle-earth mankind's guardian, eternal Lord, afterwards prepared the earth for men, the Lord almighty.

To me, there seems an uncommon pertinence in this story to our situation as pilgrims in the crepuscular frontiers of verse, and literacy in general, in the West. Among the ghostly company of those whose patrimony we so revere, our tongues may feel cold and dumb. Not only here, but at the nativity of the Lord, we can be thankful that shepherds were called upon to sing alongside the immaculate tongues of the angels. Furthermore, the imperative to sing of the principium creaturarum, could be understood to mirror the initial shape of all creation: a simultaneous drawing-up-into-being from the ambiguity of non-being, as the God who ‘makes the fisherman most wise’ creates the world out of nothingness, prophets out of stutterers, poets out of herdsman, and gods out of men. This he does with the utmost delicacy: the man is not destroyed in the god-making, the herdsman is preserved in the poet, the stutterer retains the diamond of his personhood.

From what I have read of David Foster Wallace, it seems that his problem was that he thought he would be committing some sort of infidelity towards authenticity if he left himself behind and madly pursued the Beautiful. Those karmic braids which remember up to 100,000 sins laying behind him, shorn. Of course, it is for this reason that his writing has effected a catharsis for multitudes of the existentially perplexed, and has afforded me the insight to be able to say what I have: in any case, I may be wrong. No man can know the depths of another man’s heart.

Steiner posits in The Grammars of Creation that the libidinal wing-beat toward personal infinitude and immortality is one that has united makers from the most ancient times with the present. Thus, we are united in our metaphysical narcissism. We will talk more about this, its truths and untruths, at a later time. For now, I would like to say that the fundamental instinct of the maker, and of poets especially, is in the abstruse and inconsolable hope that all things will be in God somehow preserved, and the reply of the heart to His gratuitous kenosis in doxology. It is in this shared wound of hope and gratitude that poets feel, I think, the most veracious sense of brotherhood and sisterhood. Those imperfect but memorable lines of Nabokov:

I’m ready to become a floweret Or a fat fly, but never, to forget. And I'll turn down eternity unless The melancholy and the tenderness Of mortal life; the passion and the pain; The claret taillight of that dwindling plane Off Hesperus; your gesture of dismay On running out of cigarettes; the way You smile at dogs; the trail of silver slime Snails leave on flagstones; this good ink, this rhyme. This index card, this slender rubber band Which always forms, when dropped, an ampersand, Are found in Heaven by the newlydead Stored in its strongholds through the years.

Or the Russian Martyr, Pavel Florensky, saying:

“Everything passes, but everything remains. This is a cherished thought for me, that nothing goes away for ever, nothing is lost, but somehow, somewhere, stays. Its worth remains, although we cease to perceive it. And our labors, even if everyone forgot about them, remain and somehow give their fruits. And for this reason, although I regret the past, there is a living sense of its eternity. I did not part with them eternally, but only in time. And it seems to me that all people, whatever they might think, feel the same in the depth of their souls. Without this, life would become senseless and empty.”

― Letters from the Gulag

Forget about yourself in the face of the Beautiful, and start writing. Your life will change without your realizing it. One day, you may find yourself no longer a hypocrite. Dante was a pilgrim, and so are we.

God didn’t bring me that copy of Blake so that I could become an corpulent hamster-wheel of mentation, but so that I could begin to learn the language spoken in eternity, the language that He speaks, the language that He articulated just for me.

I must lie down where all the ladders start In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

-Yeats

As I have proposed elsewhere, poesy is a subset of that catholic telos of theopoiesis which so completely honours man that he must needs blossom in praise and thanksgiving.

Eventually, the candy-wrappers and the hotdogs and kid's-meals and the youtube reels and the nakedness and the lies will all be seen to have led you right back to the garden.

Don’t scorn the base things, and don’t be their slave, either. Many of us have, out of a twisted meekness, given over to despair. Find a Virgil, fall in love with a Beatrice, and follow them to Paradise.

The Providential Reader is every single person. Perhaps all they can read is that you do not mock what others mock, or praise what others praise. That may be enough in the end. Glory to God for all things.

Sorry to have read it so late, but it was really powerful. Thanks for sharing.

This is beautiful. It reminded me of Dn. Nicholas' conversation with Fr. Silouan; have you seen it? https://thewoodbetweentheworlds.substack.com/p/replay-the-need-for-cultivated-imagination