“Let God arise, let His enemies be scattered, and let them that hate Him flee from before His face.” Psalm LXVII

Among the credentialed class, it has become commonplace to hear the words “problematic” and “Bible” in the same breath. A glance through the books of the Old Testament quickly reveals why, not unreasonably, a deracinated, religiously illiterate individual would come to this conclusion.

You'll often hear imprecatory psalms cited as proof of the unacceptability of Scripture as a moral foundation for contemporary society. “Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones.” That’s not very nice.

And “That’s not nice! That’s stupid!” was essentially the rallying cry of the new atheists in the early aughts. The seemingly urbane and rhetorically formidable Christopher Hitchens spearheaded this crew. A man who for some years trotted around the globe like a gleefully outraged Santa Claus, pulling from his velvety bag of insults one whiskey-infused lashing after another for whichever unsuspecting religious person had the misfortune of existing in his evangelical orbit.

The Bible is stupid and evil—more and more Americans, on the one hand, softened by the mass affluence of the 90s and, on the other hand, hardened by the full-frontal assault of a supercharged Simpsonesque irony, tended to agree. “Hey, this Bible really is filled with all sorts of unsavory characters, Homer!”

As a 90s kid raised in a household with a social worker mom who self-identified as a recovering Catholic, and an agnostic dad with no real religious background who taught toddlers with special needs, I was raised in something resembling the ascendant morality; this is a set of beliefs which researcher Christian Smith calls Moralistic Therapeutic Deism: Be nice, don’t judge, tell the truth, and of course pursue happiness—whatever that means. Oh, and if there is a God, it’s certainly not a God who talks to people or makes it rain frogs. This is a simplification, but I think a more or less fair one.

To be fair again, there are worse belief systems than MTD. My parents are thoughtful individuals who have spent most of their adult lives working with the underprivileged and inconvenient. They also raised two children in a loving, stable home and are upright, integrated community members by all other traditional measures of civil and familial duty. For that, I am eternally grateful.

Though we didn’t go to church, neither of my parents were atheists, and discussions surrounding religion were from a respectful anthropological point of view (both are former archeologists) with perhaps the occasional off-colored joke. We watched a lot of Monty Python.

Thankfully, I was blessed with a father who had an abiding love for old books. The Brothers Karamazov is his favorite novel, and I have a vivid memory of my father howling with laughter as he recalled the story from that novel of an atheist philosopher who, upon dying, was astonished to find himself in the afterlife, and sentenced by God to walk a quadrillion kilometers before he could enter paradise. Indignant, he laid down for a thousand years before finally giving up and walking the distance to receive his reward (I would find out upon reading the book that later in the story, the atheist declares that the walk was worth it for a few moments in paradise).

Our living room bookcase was lined with beautiful hardcover Heritage books, from Livy to Beowulf to Melville, which I was encouraged to peruse. My dad read me The Lord of the Rings trilogy as a bedtime story multiple times. By today’s standards, this would make him some species of right-wing extremist. My mother is also an artist, and we grew up with a ceramics studio in our garage. Growing up in a small town in Appalachia, I had a relatively cultured upbringing.

One Christmas as a young teen, I tore the glimmering wrapping paper off of what I surmised was some hefty tome. Revealed was The Complete Works of William Blake. I had been reading big, old books for a year or two and had quietly supposed this made me rather clever. But nothing I had read prepared me for the landmines I would stumble over that Christmas vacation, such as:

“The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.”

“The eye altering, alters all.”

“If a thing loves, it is infinite.”

“Imagination is the real and eternal world of which this vegetable universe is but a faint shadow.”

I didn’t know what the hell any of it meant, but I knew it set my brain on fire. Possibly more. Within a few short months, I had converted—to what exactly, I’m not sure. But I secretly determined to become a poet of some renown, as you do, and embarked on an extensive reading list, in large part guided by my newfound master, Blake:

“The stolen and perverted writings of Homer and Ovid, of Plato and Cicero, which all men ought to contemn, are set up by artifice against the Sublime of the Bible; but when the New Age is at leisure to pronounce, all will be set right, and those grand works of the more ancient, and consciously and professedly Inspired men will hold their proper rank, and the Daughters of Memory shall become the Daughters of Inspiration. Shakespeare and Milton were both curb’d by the general malady and infection from the silly Greek and Latin slaves of the sword.”

“Rouse up, O Young Men of the New Age! Set your foreheads against the ignorant hirelings! For we have hirelings in the Camp, the Court, and the University, who would, if they could, for ever depress mental, and prolong corporeal war…We do not want either Greek or Roman models if we are but just and true to our own Imaginations, those Worlds of Eternity in which we shall live for ever, in Jesus our Lord.” (From the preface to Blake’s poem “Milton”).

First, I dashed through Paradise Lost in an unreflective fit of enthusiasm. I was mostly bored. I tried Shakespeare next, but in an instinctive act of ego-preservation, I decided to hold off for a spell. But after that, I made my way to what Blake called “The Great Code of Art,” The Bible. Specifically, I found inspiration in the poetry of the Old Testament.

Unlike Blake, who taught himself ancient Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, and who painstakingly crafted his own complex mythology, I was merely swept up in the thundering, richly imaged proclamations of the Hebrew prophets and the other poetic books of the OT, sifted through King James English: “He setteth an end to darkness, and searcheth out all perfection: the stones of darkness, and the shadow of death.” (Job 28:3). Very metal.

Compared to MTD, my covert albeit ramshackle poetic enterprise provided a meaningful mission with the bonus that it allowed me to play the part of the prince in disguise, a temporarily satisfying form of perverse private boasting. Most high school students weren’t reading Blake and those boring poetry bits of the OT. But like it never occurred to me that I wasn’t the only high school student writing bad poems, little did I know I was certainly not unique in being swept up in the current Zeitgeist, which, unbeknownst to everyone, was soon coming to a close.

Imagination, Memory, & The Digital Catastrophe

In my senior year of high school, I bought a t-shirt with an illustration of Albert Einstein on the back, decked out in Hawaiian regalia, complete with sunglasses and a ukulele. At the bottom was a quote from this obviously super cool outsider: “Imagination is more important than knowledge”, a declaration that could have come straight from the mouth of my visionary master Blake. Now is not the time to get into the weeds of the Blakeian worldview; it’s enough to say that through his illuminated manuscripts, Blake saw himself battling against what he considered the deadening and dehumanizing effects of an increasingly mechanized, calculating worldview (see Industrial age London) ushered in as he saw it through such heralds as Newton and Descartes.

His weapon of choice against these “Dark Satanic mills” was the self-centered Imagination: “All Forms are Perfect in the Poets mind. but these are not Abstracted nor Compounded from Nature but are from Imagination…” and he saw the Hebrew Prophets as the examples par excellence of men of the Imagination, emboldened through inspiration to confront the powers that be in defense of the downtrodden. I thought joining this battle was obviously way cooler than being nice and not judging people.

In his mindbending book Human, Forever, James Poulos juxtaposes conceptions of imagination against those of memory. He notes that after the fall of the Third Reich, the ascendant American Empire made it clear that the German people's collective and personal memory must be scrubbed. The heart of Nazism was, in turn, traced back to fascism, a sufficiently nebulous and nefarious category spawned in the murky, patriarchal past. Umberto Ecco associated fascism with “the cult of tradition.”

In its place grew a new, seemingly interconnected world led by America and made possible through the imagination-centered electric media like the television, a world Marshal McCluhan famously called the global village. At the vanguards was Disney. The company's fantastical and sterile world, a quasi-mythological stand-in for America, could safely be disseminated across the globe. Yes, we see Mufasa die. But we are not shown the blood.

After the Disney princesses and their Hollywood collaborators seized control of the means of imaginative production, foreign lands were helpless before the electrically-infused American way of life, which came flooding in to fill refrigerators, dresser drawers, and garages, all while emptying and rerouting bank accounts.

In 1999, Time Magazine chose German-born Albert Einstein as the Person of the Century. Back to my old t-shirt, the full Einstein quote reads:

"Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution."

After WWII, Einstein became a leading figure in the World Government Movement, his tongue-out photograph serving as one of the emblems of Imagination, Inc. and its seeming triumph over the oppressive and, possibly worse, stuffy old world.

In The Gutenberg Galaxy McCluhan stresses that The Reformation would not have been possible without the printing press, setting the sacred word equally before all believers without mediation from church, university, or monastery. One of the many transformations the mass replication of texts would unleash was the formation of more homogeneous cultures. A good deal of idiosyncrasy and oddity was left on the printing press room floor. At the same time, part and parcel of the Gutenberg revolution was the inevitable overwhelming flowering of competing interpretations as individuals gained access to knowledge and traditions from which the old scribal order had once shielded them.

In the 20th century, the electric medium took a world conditioned by print and turned it into Global Village Studios, where movies and TV quickly overpowered the old stories that had been gutted of much of their strangeness, texture and horror—the middle realm of angels and demons—through centuries of emphasis on the printed word and its accompanying visual-bias.

(During his life, it was said that John Milton’s Paradise Lost was on the bedside table of every landlady and shopkeeper in England. This is likely an exaggeration, but it makes a point. In the hands of a master of the print medium (17th cent.), the extra-Biblical account of an angelic rebellion before creation was too good to resist, despite having no scriptural backing and the apparent effort involved in engaging with Milton’s titanic verse. Now imagine trying to convince some Joe off the street from the 1960s to read Paradise Lost for two hours instead of watching 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s preposterous.)

Paradoxically, that very strangeness propped up the old stories and made them comprehensible and compelling to your average Tom and Sally. As many are now relearning in the digital age, the world is far more bizarre and occupied than the comparatively uniform straitjacket of print or pre-digital electric media would have us believe or imagine.

Poulos points out that digital phenomena share many characteristics once reserved for spiritual forces, such as being in two places at once, passing through walls, or inhabiting various household items. He also sees the worst as having already happened. I graduated high school in 2007, the year the first iPhone hit the market. That year, Poulous says, without realizing it, “we all became cyborgs.” Instead of providing the means for total dominance, the digital "betrayed us...against our faith that our imagination was everything highest, truest, and best in ourselves." What particular danger does our technology pose to our human being? In short, a crippling existential doubt in the face of an unfeeling, unquestioning, unsleeping machine memory, exact and unfleshed in its recall and propagated by its hosts’ insatiable appetite for “social” media. Through this silicon sieve must pass all of recorded human tradition.

Poulos points out that while ancient and medieval people did not have a strict separation between imagination and memory, by today’s conventional conceptions, they held human memory, not imagination, in awe. He compares Thomas Aquinas, that great master of synthesis, with Einstein as the genius of an age. Even his brainiac friends were dumbstruck by his ability to recall anything he read or experienced and integrate it into his mind.

In his criminally neglected book The Discarded Image, C.S. Lewis writes from the heart of the electric age:

"In a savage community, you absorb your culture, in part unconsciously, from participation in the immemorial pattern of behaviour, and in part by word of mouth, from the old men of the tribe. In our own society most knowledge depends, in the last resort, on observation. But the Middle Ages depended predominantly on books. Though literacy was of course far rarer then than now, reading was in one way a more important ingredient of the total culture.”

Insert your favorite depressing comment about literacy here. On the Middle Ages he continues:

“They are indeed very credulous of books. They find it hard to believe that anything an old auctour has said is simply untrue. And they inherit a very heterogeneous collection of books; Judaic, Pagan, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoical, Primitive Christian, Patristic. Or (by a different classification) chronicles, epicoems, sermons, visions, philosophical treatises, satires. Obviously their auctours will contradict one another. They will seem to do so even more often if you ignore the distinction of kinds and take your science impartially from the poets and philosophers; and this the medievals very often did in fact though they would have been well able to point out, in theory, that poets feigned. If, under these conditions, one has also a great reluctance flatly todisbelieve anything in a book, then here there is obviously both an urgent need and a glorious opportunity for sorting out and tidying up. All the apparent contradictions must be harmonised. A Model must be built which will get everything in without a clash; and it can do this only by becoming intricate, by mediating its unity through a great, and finely ordered, multiplicity. This task, I believe, the Medievals would in any case have undertaken.”

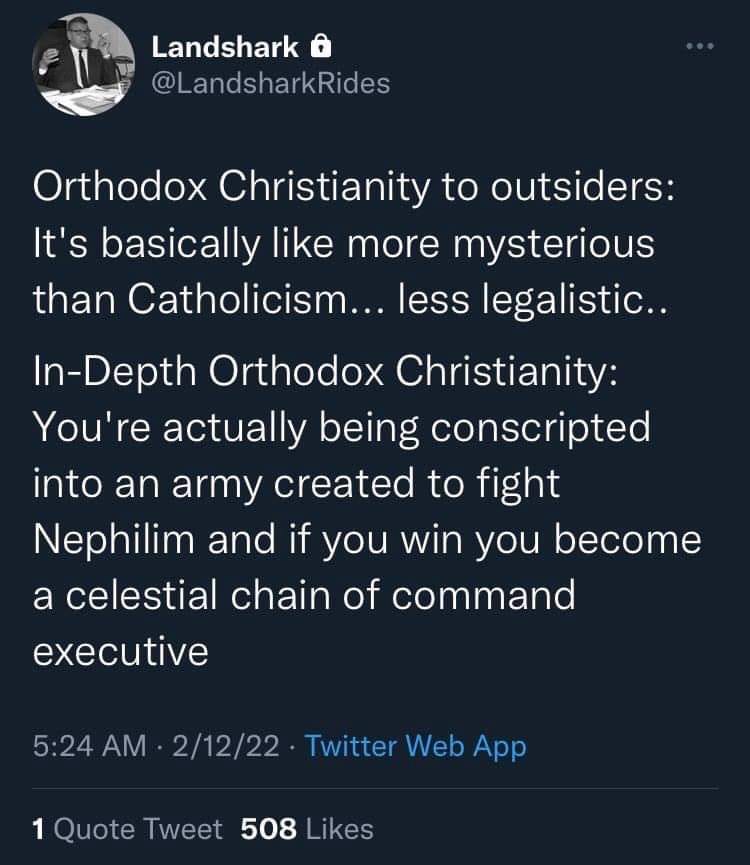

Are we not each, to one extent or another, undertaking such a project? Instead of a “very heterogeneous collection of books,” are we not inheritors of a very heterogeneous collection of not just books, but images, videos, podcasts, tweets, apps, scientific & political theories, etc.? The once monolithic Disney is now just another streaming service flowing into the collective imaginarium. A robust and inherently uncontrollable digital pluralism has usurped the uniformity of the electric-age. Naturally, having passed through modernity, we are less credulous of authors and texts (see: content creators and content) but confronted with the dazzling array of raw data from all manner of traditions foreign to our own (if we are so privileged, or burdened, depending on your viewpoint, to have one), we must filter and cohere numerous fields of knowledge somehow.

Well, how do we do this?

e-Platforms & Kids These Days

Fast forward to 2015, and after years of working various blue-collar jobs and bumming across the US, I am now attending a small liberal arts college in my hometown. Reality TV star, real estate tycoon and all-around con man Donald Trump is running for president, and everyone is laughing for different reasons. He tweets a lot. Meanwhile, every other young male I know is inexplicably watching three-hour Youtube videos of Joe Rogan musing from the depths of a marijuana cloud about what would happen if you gave a troupe of chimpanzees DMT. At the same time, some poor beleaguered astrophysicist struggles to maintain his bearings. Young people are dying their hair bright colors, seemingly making them increasingly upset. Video games are getting more realistic.

Bolstered by the 24-hour news coverage of his enemies, Trump wins the Republican nomination by presenting himself as in direct opposition to everyone and everything thrown at him. More laughter. The legacy media apparatus assured the American people that there is no way this guy could lose to arguably the most unpopular politician in the world, Crooked Hillary Clinton.

I went to bed one night as someone with a lifelong, almost principled disinterest in current affairs and woke one morning astonished to discover that current affairs were, suddenly, rather interesting; after months of being reassured that a Trump presidency was impossible, The Donald had become the first post-modern president of The United States of America. Trump had tweeted his way into the White House. The haters and losers seethed. The online ones certainly did. From observing the media, I would have expected rage or the weeping and gnashing of teeth the day after the election from the student body. From my somewhat detached perspective, there was a feigned somberness on campus for a few days but no one seemed that upset.

Born the year Bush senior was elected president, I was nearly a decade older than the youngest freshman, a considerable but seemingly non-alienating difference. But I was struck and genuinely alarmed by the marked difference in demeanor between myself and the faculty on the one hand and the Zoomer student body on the other.

A noticeably flat facial affect was common. While one can expect 18 and 19-year-olds to be a bit clueless, their ability to perform the most basic social norms was often comically absent. Of course, they were mostly on their phones. There were exceptions. I was on the soccer team and my teammates were energetic, suitably inappropriate, and genuinely fun to be around. The theater kids I got to know shared these qualities, which I chalked up to how they constantly flopped onto each other in class, in the hallways, and, I have to imagine, in the dorms. These young people still had a connection to the body.

Smartphones were ubiquitous. I got my first flip phone when I was 18, and my first smartphone at 25. And then I too willingly became swept up in the algorithms. Youtube was my poison of choice.

Amidst the chaos of the new Trumpian public square, another character appeared onscreen. The now infamous Dr. Jordan Peterson, a Canadian professor and clinical psychologist, came to public attention through the culture war, specifically through his recorded refusal to adhere to a linguistic shibboleth surrounding gender pronouns which he posted to Youtube. He shot to prominence soon afterward when his backlog of college lectures on the intersection of psychology and mythology became popular, particularly among young men.

In the spring of 2017, this self-professed agnostic, who cites Jung as his preeminent influence, began a lecture series on the book of Genesis. Despite his heterodox views, Christian and secular viewers alike resonated with what they saw as his honest grappling with the Biblical narrative that Peterson rightly claimed undergirds Western civilization.

Whatever one thinks of Peterson, he was the first public figure since Hitchens to initiate a large-scale public discussion around religion. Unlike his British predecessor, Peterson was far more mythologically literate and, while more than capable as a debater, remained open to dialogue.

Talking heads became concerned that this “alt-right” figure was another sad symptom of a larger plague. With the rise of arch-pugilist Trump through the platform Twitter, the digital technology meant to further strengthen the grip of the legacy media and their allied elites suddenly, painfully, could no longer be considered an unqualified good. It was raining anonymous frogs and the Egyptians were none too pleased. The rhetorical insult stick Hitchens used to beat those stupid Fundamentalists over the head was now used by the POTUS against experts, newscasters, and celebrities alike. Even worse, people who drove trucks were laughing and cheering him on! “Trump isn’t very nice! He’s stupid!" (and likely evil) became the new mantra.

But far more than Trump or Peterson, I would become interested in the individuals who stepped into the conversational space opened up in the wake of Peterson’s biblical lectures.

While the culture war heated up, I continued my studies in English and digital media while spending most of my spare time investigating historical Christianity. Though I had some familiarity with the text of Scripture and the more esoteric forms of Christianity such as Blake’s, Swedenborg’s, or The Golden Dawn, I only had the faintest grasp of what professing Christians actually believed. I had always been a voracious reader, but between 2015-2019, armed with my new portable computer (my smartphone), I found myself sucked into the aural-visual space of Youtube.

Fast forward to the tail end of my undergrad degree, I began attending a nearby Orthodox parish (actually, the first parish I attended turned out to be a schismatic Old Calendar church, but that’s another barrel of fish). I won’t go into the soap opera level story leading to this unexpected outcome. However, if I had to describe my conversion in one word, it would be traumatic.

That summer, when I first sat down with my now priest and laid out my life story, he asked me what I had been reading and watching. I recall mentioning Fr. Seraphim Rose, Dostoevsky, and Kallistos Ware, all pretty standard fare, and then three Youtubers: Orthodox artist and storyteller Jonathan Pageau (he had heard of him and liked his work), Orthodox apologist and comedian Jay Dyer (heard of him, didn’t know his work but had heard mixed reviews), and Christian Reform Church minister Paul Vander Klay (never heard of him).

Looking back, the time I spent on Youtube with these three men, their work, and the online communities surrounding them had the most significant impact in the years leading to my conversion.

Christians of Youtube: Pageau, PVK, & Dyer

Of the three, I first came across Jonathan Pageau when a video popped into my Youtube feed titled The Metaphysics of Pepe on Jordan Peterson’s channel. That video was instigated by a slew of online poasters pointing out that he sounded like Kermit the Frog (he does). Peterson had known Pageau before his status rocket and knew he was a symbolically savvy individual.

Pageau explained that the frog is a liminal figure inhabiting both land and water and that the online Right, marginalized in the digital public square, identified with this frog figure because they were at once the purveyors of mocking humor usually associated with chaos, as well as the advocates, however crude, of those traditional norms that were now considered deplorable. ‘Oh ok, cool. There’s a kind of Robert Bly thing going on here,’ I thought. Pageau went on to connect the frog phenomenon with the prophet Elijah who mocked the prophets of Baal as part of his mission to restore order to Israel.

Following this appearance, Pageau created his own Youtube channel from his home in Quebec after a flood of requests for symbolic analyses reached his inbox. The son of a Baptist pastor, Pageau is an adult convert to Eastern Orthodox Christianity who, together with his brother Matthieu Pageau had developed a symbolic lens of seeing the world through the study of the Church Fathers and ancient rabbinic texts.

He made connections between the patterns found in The Bible and the patterns found in our day-to-day experience, often drawing examples from popular films, fairy tales, and the most mundane examples from everyday life, such as shaking hands.

His Youtube channel features such titles as: Adam and Eve…and Batman, Star Wars: The Last Jedi | Dismantling All Order, and Symbolism in Shrek | When the Marginal Wins.

Over the next few years, it became harder for me to dismiss the connections he helped me make between the patterns found in Scripture and those I found in reality as mere esoteric hermeneutics. An Orthodox icon carver, he wove together the language of iconography, church architecture, stories of dog-headed saints, and the writings of the Church Fathers into a coherent tapestry, strange as it was beautiful. I remember thinking, “if only this were true.”

Similar to my experience upon first encountering Blake, this lens for seeing the world made intuitive sense to me, although I wouldn’t have been able to explain it to you if you had put a gun to my head. Unlike Blake, this was not the limit-smashing self-made spirituality of the lone artist, but a hierarchical world of sight, smell, sound and touch, filled with angels and demons and which included and was as accessible to the babushka as much as the philosopher. It was a world I could inhabit, not one that required my own creative or imaginative faculties. I will not attempt to explain this way of seeing the world as text is not the ideal tool for explaining it, and frankly, I’m not that good at explaining it.

In Christian Roy’s article Marshal McLuhan and Eastern Christianity: Probing an Interface with the Symbolic World in Mind he notes that Pageau’s form of cultural criticism “has taken an essentially oral, dialogical form in the neo-acoustic environment of electronic social media” and that “these new media retrieve certain features of pre-print and even preliterate cultures, e.g., in that their information overload favours instant symbolic pattern recognition over sequential dialectical exposition.”

For me, Pageau facilitated a series of epiphanies that put the role of art in its proper place: not as a mere individual expression that is an end in itself, but as the ability the artist possesses to help knit a community together through various forms of craftsmanship. At its highest levels, the artist helps to reveal the sacred.

On top of that, as someone coming from what I would now consider an occult background, I had always been struck by how so many modern Christians seemed oblivious or disinterested in the middle realm of angels, demons, saints, djinns, fairies, etc. Pageau’s engagement with this realm laid the groundwork for what the popular podcast The Lord of Spirits has now taken head on—the mythological backdrop of the cosmos from a Christian, specifically Orthodox, perspective.

The next channel the algorithm fed me was a bushy-bearded Paul Vander Klay (PVK), who pastors a small church in Sacramento, CA. Drawn by Peterson’s ability to do what Christian ministers have been unable to for decades (make former and non-Christians reconsider the value of the Christian faith), he began a commentary series on Peterson’s Genesis lectures. True to the Protestant work ethic, PVK began pumping out nearly daily one to three-hour videos, using Peterson’s Biblical series as a springboard to slowly chew on various religious, philosophical, and historical factors and questions, drawing from a host of sources both past and present, from St. Augustine to C.S. Lewis to contemporaries like Pageau or cognitive scientist John Vervaeke.

His videos, which are themselves a collage of videos, continue the medieval project of synthesis; like many online commentators, he is struggling towards a new model that can synthesize and encompass the multiplicity of our present time. I’ve found few individuals online with his mixture of gregariousness, an openness to learning and criticism, and the ability to model productive dialogue.

His comfort in dialogue partly stems from having a rooted tradition from which to explore. A third-generation Dutch Reform minister, he has something few Americans have, a serious and engaged generational religious continuity.

Both he and Pageau spent several years in missionary work in third-world countries. These experiences afford a certain distance when analyzing or contextualizing current trends. But perhaps PVK’s most significant contribution has been his ability to foster relationships through sustained dialogue with those from other traditions. The cognitive scientist John Vervaeke, a former colleague of Peterson at the Univeristy of Toronto, along with Pageau, have formed a friendship with the affable and open pastor, the three of them even meeting recently in person to discuss what Vervaeke has called The Meaning Crisis.

One staple of PVK’s channel is the recurring “Randos” slots where anyone can sign up for an extended conversation with him over Zoom. These conversations are often with people struggling in one way or another with faith. Many conversations make it onto the channel while many stay offline for personal reasons. I’ve spoken privately with him myself, and I think he is a genuine mensch. When discerning the faith, seeing a Christian modeling fruitful ways of relating to the world goes a long way.

Enter the dread Jay Dyer, aka the meanest man in Christian apologetics. He’s been called a conspiracy theorist, a snake oil salesman, a real jerk, and my favorite, a KGB sorcerer. I first encountered Dyer on Warski Live in the heyday of bloodsport-style internet debates. He was debating an atheist, JF Gariepy, on theism. I recall JF invoking a hypothetical alternative universe occupied by self-determined meat machines to support his materialist worldview. The majority of the debate was Jay pointing out the impossibility of anyone living out such a worldview. The debate essentially was won when JF snapped at the host and admitted he wasn’t making his own arguments. They were just a chemically determined process.

Dyer is often criticized for being too severe, rude, uncharitable, or just plain “extreme.” This could be for arguing with clergy, calling an argument “low IQ and lame,” or making a two-hour video refuting what to a layman would seem a minor theological issue. Dyer takes seemingly minor theological matters as seriously as fans of what he calls sportsball take their favorite teams (if you’ve met a dedicated sports fan, you know there are really no minor issues). On the other hand, he is characterized as an unserious character, in part due to his forays into comedy (many of his impressions are funny: Zizek is my favorite) and his, at times, expressionistic online presentation, influenced in part by the unofficial Dyer channel mascot, Nicholas Cage. He is also dismissed for his “conspiratorial” analysis of geopolitics, i.e., the convergence of NGOs and the tech and entertainment industry with various intelligence agencies. While Pageau will analyze films from a more phenomenological perspective, Dyer will more likely analyze films with propaganda in mind.

From his telling, Dyer had a long and at times torturous journey into Orthodoxy. Coming from an evangelical Baptist upbringing, he transitioned into a more intellectually robust Presbeyterian-Reformed tradition as a young man, then converted to Roman Catholicism before finding his home in the Orthodox Church after a period of questioning the Christian faith. With a Master’s degree (ABT) in English and Philosophy, On paper, he is equipped to evaluate different Christian worldview claims from a propositional and experiential level.

I have heard Jay say on multiple occasions that he wished someone had provided him with the information he presented. To my mind, he is someone who, by his nature, couldn’t help but agonize over finding the truth and would like to spare others as much of that angst as possible. He has also remarked that he would prefer not to do Orthodox apologetics and instead be able to focus on more creative pursuits, but that there is a dearth of robust but inquirer-friendly information.

Although this is slowly changing, I found this to be true. This may strike one as absurd. There is, after all, a seemingly endless fount of online information on Orthodoxy. But when I began investigating Orthodoxy there were few one-stop shops or public-facing Orthodox clergy presenting detailed analysis and/or criticism of such a wide range of issues as higher criticism, the formation of the canon, sola fide, the eucharist, apostolic tradition, etc. Regardless of the faults or merits of his approach, what he provided for me was a consistent human presence covering, week in and week out, a wide range of topics through the medium of Youtube and other social media which you could interact with, even for all the limitations inherent in that technology.

(For some perspective, Patristic Nectar, the most well-known Orthodox channel fronted by a clergyman (Fr. Josiah Trenham), began making regular content on Youtube in 2019. However, it should be noted that on that Youtube channel, comments are turned off, and there are no livestreams.)

I’m not qualified to evaluate Dyer’s defense of these topics with any authority but I found many of his arguments compelling and helpful, as have many others. For instance, when my professor of religion at undergrad went out of his way in a class on the Old Testament to point out inconsistencies in the different Gospel accounts, I was familiar with his historical-critical presuppositions and could guess his intentions.

We should remember that in an environment characterized by information overload, in-depth analysis is deemphasized, and in turn, differences are flattened over time. It has long been lamented that the public has become less informed as exposure to information increases.

In his book The Revolt of The Elites, Christopher Lasch has a chapter titled “The Lost Art of Argument.” In it, he juxtaposes the unmediated presidential debate between Lincoln and Douglas against the press-mediated debating format of his own time, which required its participants “to rely on their advisers to stuff them full of facts and figures, quotable slogans and anything else that will convey the impression of wide-ranging, unflappable competence” and “tends to magnify the importance of journalists and to diminish that of the candidates.” In the Lincoln-Douglas debate, by contrast, “They subjected their audience to a painstaking analysis of complex issues. They spoke with considerably more candor, in a pungent, colloquial, sometimes racy style, than politicians think prudent today.”

When debate becomes a lost art, information makes little impression. Lasch sums this up nicely: "When we get into arguments that focus and fully engage our attention, we become avid seekers of relevant information. Otherwise we take in information passively—if we take it in at all.”

Youtube has returned debate to the public square, although mediated by the digital. The biggest drawback to the digital mediation of debate I can see is that it is impossible to punch another man in the face through the internet, the possibility of physical assault being the best deterrent to “crossing the line.” Regardless, for all the negative aspects of Debate Me Bro culture, argumentation provides an opportunity for clarity which is sorely lacking in current public life. The online debate culture is unsurprisingly most popular with young men. And, of course, anyone today with a fully fleshed-out worldview and claims to epistemic superiority is perceived by many as offensive. But in an age that is hesitant to define what a man or a woman is, it should behoove every sane person to pause a half-beat longer before chastising those willing to draw hard lines in public.

Authority, Hard Lines, & The Winsome Wars

Venkatesh Rao’s evergreen article The Internet of Beefs highlights the negative side of internet combat, where storied digital “knights” fight for the loyalty (and often money) of anonymous hordes of “mooks” which can be directed against opposing knights. Rao notes that for most knights, “mooks are not important,” and “knights are neither responsible for what the mooks do, nor accountable for the views held by mooks who fight under their banners.”

Any public figure with a social media presence participates in this dynamic to one degree or another. Dyer often comes under fire for taking this dynamic too far. That is, rallying bands of mooks against opposing knights. He is not apologetic about battling worldviews out in the open or drawing hard lines. Social media is built on bad blood. A carefully curated selection of remarks taken out of context from Dyer’s thousands of hours of videos and/or social media jousts would leave anyone who has never encountered his work before to assume this guy was a giant jerk. These algorithmically influenced snapshots are simply inevitable in the new social landscape.

However, the knight-mook relationship is not necessarily unhealthy; at its best, this can be a beneficial relationship where mooks exchange loyalty and financial support for insights and connections of genuine value. Granted, under digital constraints, more unworthy knights exist than worthy ones. An unworthy knight will, at best, waste a mook’s time and, at worst, send them spiraling into an existential tailspin, often with a lighter wallet.

My trust in PVK, Dyer and Pageau was in part predicated on their insistence that they had no spiritual authority over their audience and the willingness to admit their own faults at times without coming off as pietistic. I trusted that all three genuinely desired to help their fellow man. They also repeatedly stressed the importance of joining an on-the-ground church body. Their specific recommendations speak to their general approach to cultural engagement: PVK: join a church, Pageau: join a traditional church, Dyer: join a canonical Orthodox Church, and within an American context, it’s probably best to avoid certain jurisdictions (GOARCH).

PVK has repeatedly stated, “I am not your pastor!” after people online insist, “you are my pastor!” This “I am not your pastor!” is more difficult to accept within a Protestant framework than Dyer or Pageau’s “I am not your priest!” which is obviously true; you can hear a sermon online from any Joe or Sally these days, but from an Orthodox perspective you can only receive the body and blood of Jesus Christ from an ordained Orthodox priest.

PVK has taken an interest in the rise of Orthodoxy in America, pointing out that as the pre-modern Orthodox tradition comes into deeper contact with protestant America, the Church will have to incorporate converts with a radically different set of cultural and religious priors. Change, even if it is not doctrinal, is inevitable.

Dyer and Pageau are examples of this phenomenon. For better or for worse, and for younger adults in particular, these two laymen are the most well-known evangelists of Orthodoxy in the online English-speaking world. Thousands have joined the Church because of their work. It is telling that both are former protestants who have excelled in the new aural-visual space of Youtube, in part through engagement with popular American culture. Both have the blessings of their bishops and frequently speak with clergy online, but what does it mean for church hierarchies when laymen potentially have more influence over their congregations than the clergy?

Another former protestant and layman Orthodox apologist, Perry Robinson, the OG “mean” formally philosophically trained Orthodox apologist, remarked in a recorded discussion on his Youtube channel Energetic Procession that:

“The defining issue in my opinion for this century as far as the Church is concerned, as far as our survival as Christians, will be what the boundaries of the Church are, will be Church discipline…Where are the boundaries of the Church? Can you establish them by discipline? Because if you can’t, you’re finished.”

You can get as grumpy as you want about individuals drawing hard lines in the sand but with the accelerating de-Christinanization of society, we are witnessing in real time what the disintegration of nominal Christianity looks like. To not draw any hard lines is to accept extinction.

In the same discussion, Robinson makes clear his opposition to para-church organizations. And he knows how these organizations can go wrong. A former employee of the Christian Research Institute (CRI), Robinson has documented the chicanery which has gone on in that organization on his website Energetic Procession. CRI is run by Hank Hanegraff, aka “The Bible Answer Man.” Hanegraff converted to Eastern Orthodoxy in 2017 and caught plenty of flak from the protestant world in doing so. He’s also come under fire from the Orthodox for, among other things, continuing his Bible Answer Man program, or shtick if you will, despite never publicly renouncing his Reformed views. In fact, he went so far as to say in one of his broadcasts soon after converting, “Look, my views have been codified in 20 books, and my views have not changed.”

Is there the ability or the willingness to discipline influential laymen when they cross the line? Where, exactly, are the lines anyway?

Robinson advocates that apologetics be done directly by the Church, suggesting that some Deacons be trained to fulfill this specific function for their respective locales. They are, as he points out, actually ordained by Christ. The credibility of his own part-time apologetic work is strengthened by the fact that he does not accept any form of payment for his efforts.

Since my reception into the Church in 2020, more Orthodox clergy are embracing public-facing apologetic work online, the most notable being Fr. Josiah Trenham who has a PhD in theology. Other notable clergy are Dr. Fr. Deacon Ananias Sorem, a professor of philosophy, and Metropolitan Jonah Paffhausen of ROCOR who is the abbot of St. Demetrios of Thessaloniki Monastery in Virginia, both active on Youtube and who have collaborated with Dyer at times.

Ancient Faith Radio (AFR), or Ancient Faith Ministries, is a department of the Antiochian Archdiocese of North America (of which I am a member) that offers a wide variety of online radio shows, podcasts, and interviews and has a large audience. However, the organization has a small presence on Youtube, the gold standard of social media influence, and no official apologetics branch exists.

AFR platforms laymen and clergy, and has come under criticism for its platforming of certain laymen who have publicly advocated for the Church to be more LGBTQ-friendly and inclusive—which many Orthodox perceive, rightly, in my opinion, to be an implied call for change in doctrine from these lay contributors. Although certainly not alone in his displeasure with this, Dyer was at the forefront of this criticism.

As a brief aside, I think many in the older generations have little conception of just how effective it is to drive home your argument when you can do a multi-hour livestream going through dozens of examples showing the subject of your criticism doing what you’re criticizing them for and responding to any objections in real-time. Remember, the internet remembers all. That deleted tweet? Yeah, that got screenshotted. That obscure blog article from six months ago? Yeah, a 20-year-old found that in six seconds. The machine memory of the internet is no joke.

The issue of credibility associated with platforms should also be raised. Dyer has a steady slot on the infamous The Alex Jones Show. It’s not for nothing that he jokingly refers to Jones as Lord Voldemort. Not that Dyer cares, but in the eyes of many, an association with the "they're turning the fricking frogs gay!" guy removes any shred of credibility. Similarly, Pageau’s recent appearances on another alternative media platform, The Daily Wire, facilitated by his friend Peterson, removes credibility. These dynamics are inevitable for public figures as they receive increased exposure.

PVK has often remarked on happily being a small Youtube channel (25K), although he has shared the stage with well-known public figures in the Christian and Christian adjacent world such as Aaron Renn, Tom Holland, Paul Kingsnorth, and yes, Pageau. His credibility comes largely from his pastoral approach to online randos and the occasional sneak peeks into his homeless ministry and local church life.

This “lowly” position has allowed him to form stable connections over time with a hodgepodge of colorful characters that larger, more commercial channels wouldn’t have the time or inclination to engage with on such a level. Running parallel to the conversation around platforms is what the ever-irenic PVK has coined The Winsome Wars. This refers to a debate primarily in the American protestant landscape that began after some pointed public examinations of PCA pastor Tim Keller’s perceived toothless, albeit New York Times-endorsed winsome cultural engagement strategy. PVK has often noted that one of the easiest ways to grow on any social media platform is to find your tribe's favorite enemy and attack them effectively.

While PVK’s online ministry, which is centered around his own winsomeness, has won him numerous friends and provided succor to many struggling with their faith, his denomination is in the process of splitting over same-sex issues. Or you might say hard lines are being drawn.

As PVK also is fond of pointing out, in the Judean culture war of the day, the only thing the warring factions could agree on about Jesus of Nazareth was that they would all be better off if this troublemaker was dead.

Orthobros & Discord Bringing Us Together

Bro, really? You’ll have by now noticed that the word bro carries certain negative connotations in the broader culture. To be a bro implies immaturity, self-satisfaction, and, worst of all, an unapologetic embrace of machismo.

To be a bro also implies other bros. Saddest of all is the lonely bro. Whether it’s gym bros, stoner bros, preppy bros, or bro bros, few happenings raise the ire of today’s strutting moralist more than a feral pack of bros occupying space, laughing, grinning, shouting, trying out wrestling moves. Bros love their bros. This is toxic. This is unacceptable.

Bros can be, granted, a pain in the ass.

Unfortunately, bros have migrated mainly to the world wide web. Peterson, for instance, much maligned for having the gall to encourage young men to get their acts together, equates the habitual online use of the word “bro” with “derisive, narcissistic Machiavellian, sadistic trolls.” While this is something of an overstatement, it speaks to a reality, particularly when a digital swarm latches onto the perceived hypocrisy of a high-ranking internet knight.

The online orthobro is, you guessed it, an Orthodox guy. He is typically a younger convert and often anonymous. As a general rule, they are openly unsympathetic to The West as it stands and often cite Western theological developments as responsible for our current civilizational malaise. What “The West” is precisely is rarely defined, but it’s common to find a strong critique of the rebellious founding of The United States in particular as emblematic of global ills. Orthobros advocate monarchy.

In online discourse, the Trad Caths and some magisterial Protestants strike a similar tenor, but they will tend to see western converts to Orthodoxy as traitors of a sort, rejecting their God-given heritage. They are partially right. Although the profound failure of the older generations to actually pass on this Western heritage is sometimes acknowledged, the conversion of these native sons to Eastern Orthodoxy is an outright rejection of what many see as the pernicious Faustian spirit animating The West.

Of course, the allure of the East has been with us for over half a century now. In the mid-20th century, perhaps partially bored with the consciously non-sectarian, staid “Judeo-Christian” establishment ushered in by FDR, many Americans turned to the more exotic eastern religions in the ’60s after a decade of the highest church attendance in the country’s history. These imports came rushing in as Vatican II was in the process of dismantling the Roman Catholic Church’s liturgical grandeur.

In tandem with this influx from the East was the rise of psychedelics, The Beatles and their LSD-infused stylings at the vanguard. The charismatic and sociopathic Timothy Leary, who held the same position as Peterson at Harvard, said, “‘I declare that The Beatles are mutants. Prototypes of evolutionary agents sent by God, endowed with a mysterious power to create a new human species, a young race of laughing freemen.”

As George Harrison could attest, Buddhism and Hinduism had all the weird yet enticing trappings of pre-modern religion, now showcased for the first time in technicolor: dragon statues, mandalas, saris, elephant gods, and an endless supply of gurus and wispy bearded wise men who descended from airplane boarding stairs to peddle their own brand of pure, uncut spiritual transformation, no civilizational association required. Perhaps most importantly, for a world still reeling from World War II, you didn’t have to actually believe in any of this stuff. A neat, psychologized version of the above was commonly adopted.

A neat, psychologized version of religion may have done the job fifty years ago, but the cultural landscape has not so much shifted under our feet but suffered a series of level ten earthquakes since the 60s.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in his aptly named Substack After Babel is putting forth a case that many have intuited for years now—the children raised on digital technology, now coming of age, are profoundly unwell. Haidt conclusively refutes the criticism that all this talk of a mental health epidemic is just another classic case of “these kids these days” rhetoric; dramatic increases in teen self-harm, attempted suicide, and successful suicides since 2012, five years after the release of the first iPhone, say otherwise.

Sure, techno-optimism is a comfy pair of shoes for a well-to-do Gen Xer. But bro, have you been on TikTok lately?

I have heard it framed as a criticism that those inquiring into Orthodoxy are merely searching for something unchanging and solid in a time of significant societal flux. Well, is this not an imminently reasonable reaction? Chaotic times may account for why some look into more traditional faith communities, but in the final analysis, it doesn’t account for why they are signing up for such unfashionable programs.

Certainly part of why young men in particular consider Orthodoxy at a time when the broader society is calling them problematic pieces of crap is that masculinity is still overtly encouraged in the ancient Church.

For all the uncool people out there, Discord is a chat app similar to old-school chat rooms but with voice and video capabilities. ROCOR’s (Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia) Metropolitan Jonah Paffhaussen taught a series of catechetical lectures on Dyer’s Discord server during the COVID "pandemic," focusing on the spirituality of the Orthodoxy. In one of the first lectures, he said something to the effect of “your toxic masculinity is welcome here” with a wry smile. At the same time, this is a man who, in a homily, spoke of “the grave disease of convertitis” that is “absolutely manifest on the internet where you have all these learned arguments by great theologians who still happen to be catechumens,” and “they’re treating people horribly.”

Young men can be a giant pain in the ass and still have a legitimate need to joust with each other and make mistakes. Those are both true. It is not an excuse for bad behavior. The internet is not an ideal setting but you have to work with what you’ve got. Relatedly, red-blooded young men don’t want to “man up” and get a crummy email job. They want to participate in a great story. You’re just going to have to put up with thousands of online orthobros fantasizing about retaking Constantinople for the foreseeable future. Sorry.

Over at PVK’s Youtube channel comments section you can behold one of the marvels of the internet, something that could serve as an aspiration for online bro culture. Videos of under 2K views consistently have hundreds of comments, many of them arguing with one another, and yet the vast majority of participants are cordial even as it gets spicy. Some years ago an atheist from PVK’s in-person meet-up group who watches his videos decided to set up a Discord server, Bridges of Meaning, which soon took on a life of its own. Anonymity was accepted though using real names and photos was encouraged. Side projects, a growing network of in-person meet-ups, discussion groups, art collectives, and even marriages have come out of the server. A sizeable subsection of the server, myself included, converted to Orthodoxy. I met my wife there.

For all the warranted criticism of online communities, they afford the possibility of real connections being made. They can provide an on-ramp to on-the-ground faith community.

And contrary to popular memes, even orthobros are stepping away from their screens and going to Liturgy. As my good friend, a cradle Orthodox, has remarked on more than one occasion, “converts are insufferable, but at least they come to the services.”

In Conclusion, & Memory

In the Spring of 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 hysteria, a video montage of various Hollywood celebrities singing John Lennon’s ode to atheism, “Imagine,” was making the rounds. The top comment on Youtube put it best: The only inspiring thing here is how the internet came together to say “no.”

It would be hard to give a better illustration of the usurpation of the old media by the new. The out-of-touch electric-age pantheon of gods (celebrities) had toppled themselves by doing what they have always done: attract attention. Regrettably for them, the public didn’t particularly want to imagine there was no heaven, or countries, or possessions. In fact, from the enforced comfort of their own homes they remembered their loved ones who had passed, they remembered life in their countries as they once were, they remembered firing up their oversized grills and having a beer with friends. They remembered. This imagining crap? It’s all so tiresome.

Like my fellow parishioners, I was unable to attend the Pascha service in 2020 due to the lockdowns, lockdowns that would not have been possible without the ubiquity of new media. Each year the Church sings in the Paschal stichera "Let God arise let his enemies be scattered!" participating in Christ victory over the dark spiritual forces, the enemies of God, through his death, burial, harrowing of hell, and resurrection. That Pascha I felt totally defeated. I wanted to smash all the wifi towers in the western hemisphere.

But soon after we were permitted to return to worship and I was baptized and chrismated on Pentecost. On that day it was not the world but my soul I wanted saved. It's not a day I will ever forget.

In Scripture, memory plays a crucial role. After the name of God is spoken to Moses in the book of Exodus He says to him “this is my name for ever, and this is my memorial unto all generations.” God remembers Noah after the flood and the wind passes over the earth. Christ says “do this in rememberance of me.” Within the Orthodox Church we pray for the departed, “may their memory be eternal.”

Memory holds together each of our own individual stories, filled with all our friends, families, enemies, and sorrows, each a tiny symbolic microcosm of God’s divine memory which sustains all of existence.

To return to my father’s favorite book, in The Brothers Karamazov the elder Fr. Zosima says:

“From my parental home I brought only precious memories, for no memories are more precious to a man than those of his earliest childhood in his parental home, and that is almost always so, as long as there is even a little bit of love and unity in the family. But from a very bad family, too, one can keep precious memories, if only one’s soul knows how to seek out what is precious.”

As the disruptions and distractions of daily life ratchet up many more lost souls will be searching for a spiritual home. What is precious, what is to be remembered, is for the human family to decide and to pass on to our sons and daughters.

I can personally attest that, yes, much of what is precious we can find online, and even the debates and the hard lines that we draw can help in this. But that's not enough. We need to sit down at a table with friends and those who may one day become our friends to talk, to eat, to laugh. We need to be able to say, “Oh, taste and see that the Lord is good!”

Nathan, I just discovered your excellent piece. I am not a fan of reading off screen , so I will print it up and finish it over breakfast. Will comment more once I have absorbed all the details.

(On a surprising side-note: the guy who just repaved our driveway had a couple of work stints at St. George's Orthodox Church in PA where you got baptized- although he otherwise lives here in Ontario). Looking forward to digging into your work...

Thanks. This was interesting to read; both for your story and to get a sense of the online world. I became orthodox without seeing anything online; rather entirely through attending services and reading a few recommended book. I've been told that's the recommended route, but also just how it happened. Yet I meet people who are watching videos or reading stuff online. Good to know some of what it's about -- and that it's not necessarily crazy.