Today the word “transparency” is haunting all spheres of life—not just politics but economics, too. More democracy, more freedom of information, and more efficiency are expected of transparency. Transparency creates trust, the new dogma affirms. What is forgotten thereby is that such insistence of transparency is occurring in a society where the meaning of “trust” has been massively compromised…A vision directed toward the future proves more and more difficult to obtain. And things that take time to mature receive less and less attention.

From the preface to The Transparent Society, by Byung-Chul Han

I am not a technophobe. Those familiar with my past writings know I’ve found my faith, my wife, and my most productive creative partners on the world wide web. That said, I also do not believe that our various technologies, in particular our digital technologies, are inherently neutral; extended use of digital tech reliably produces certain negative results.

I’ve explored the digital’s relationship to the dissolution of basic patterns of human socialization (having dinner together: see here) as well as its broader implications for the faculties of imagination and memory (see here) but I would like to look more directly at what one would be abstaining from should one go on a “digital fast.”

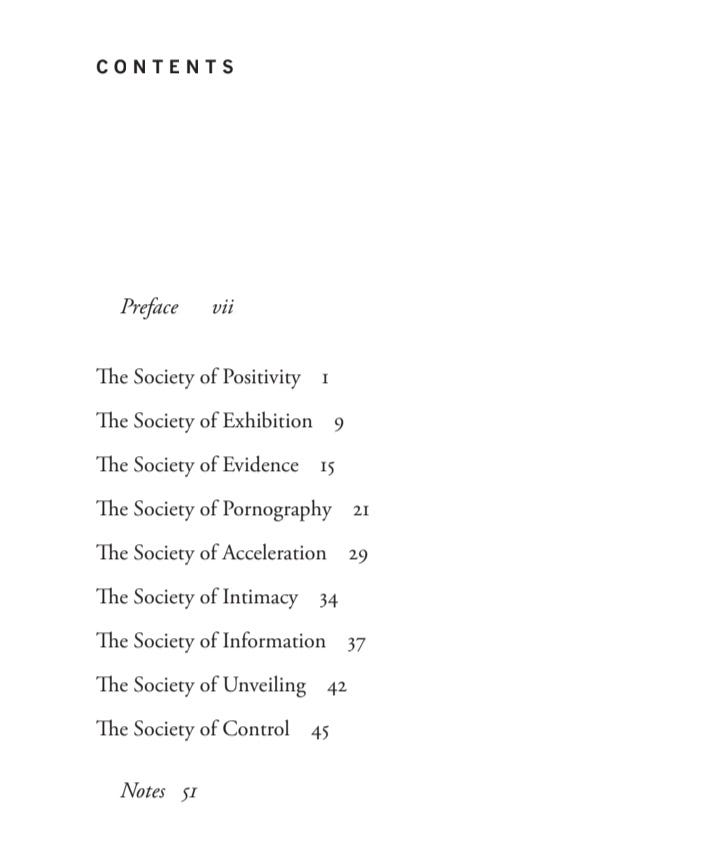

For that, we’ll peek into the excellent little book The Transparent Society (2015), quoted above, by Byung-Chul Han. In particular we’ll look at the first chapter: The Society of Positivity.

For Han, the different Societies listed in his table of contents all fall under the umbrella of The Transparent Society, which itself is made possible by the digital.

The system of transparency abolishes all negativity in order to accelerate itself. Tarrying with the negative has given way to racing and raving in the positive…love undergoes domestication and is positivized as a formula for consumption and comfort...matters prove transparent when they shed all negativity, when they are smoothed out and leveled, when they do not resist being integrated into smooth streams of capital, communication, and information.

— “racing and raving in the positive”—

Han points out that Facebook has never had a dislike button because “the negativity that rejection entails cannot be exploited economically.” With this in mind, one might recall Youtube’s recent decision to hide the dislike button count, or Elon’s short lived experiment in implementing a dislike button, sorry, “downvote” button (riiiight), on Twitter/X.

When considering the anti-social behavior so prevalent on social media this all may seem counterintuitive, but digital technology, from Uber Eats, to Instagram, to the self-checkout line at your local grocery store, are all built to facilitate a frictionless experience whereby you are able to acquire or consume more (even if that’s digital vitriol). More $10 frappes, more yoga mom content, more imported kiwis. And best of all, we are no longer required to even go inside the coffee shop, to join the yoga class, or to chit-chat with the teenage cashier.

One can begin to get the sense of how a digital fast might have implications beyond merely staying off your phone and laptop.

Most of us carry this digital, this transparent society, in our pockets, and we’d be lost without it—literally! For all its faults, Google Maps “saves” us from a lot of friction. The thing is, if we don’t want to slip off into the borg with our AI girlfriend, if we’re to remain human, we need friction: the high-level critique, the frustrated dad who can’t find the damn exit, the relationship with the slow clerk who can’t figure out how to scan the stupid bananas and has to call the manager over and you go “it’s OK, really” as the manager apologizes as he too struggles to ring up the bananas.

Part of what a fast does is expose us to ourselves by exposing us to the world without our typical comforts. As noted in part one, within a Christian context a fast is undergone in preparation for a feast. It is a journey towards a celebration of a particular event in the life of Jesus, and that journey is within the context of a larger journey towards the Kingdom of God. And a journey without friction, without something going awry, isn’t really a journey; it’s climbing Mt. Everest while lying on your couch with a VR headset.

Aside from facilitating a frictionless, false-positivity, the digital encourages something else which is antithetical to a fruitful fasting/feasting cycle—premature unveiling.

Here is Han, from the chapter The Society of Unveiling:

… the digital net, even as the medium of transparency, is subject to no moral imperative. It so to speak lacks a heart—traditionally, the theological-metaphyiscal medium of truth. Digital transparency is not cardiographic but pornographic. The goal is not moral purification of the heart, but maximal profit, maximal attention.

Han points to Jean-Jacques Rosseau and his work Confessions, tellingly itself a response and attempt to replace St. Augustine’s work by the same title. In his book, Rosseau’s call for transparency reaches the heights of categorical imperative:

A single precept of morality can do for all the others; it is this: Never do or say anything that thou dost not wish everyone to see and hear; and for my part I have always regarded as the worthiest of men that Roman who wanted his house to be built in such a way that whatever occurred within it could be seen.

Contrast this attitude with that of Mary, the Mother of God, when she is visited in a manger:

Now when they had seen Him, they made widely known the saying which was told them concerning this Child. And all those who heard it marveled at those things which were told them by the shepherds. But Mary kept all these things and pondered them in her heart. (Luke 2)

Digital fasting, like any fasting, is only fruitful if it opens us up to life and life abudantly. We cannot come to that life without some measure of suffering, of seeing our own weaknesses. And our suffereing will likely slip into masochism without pondering in our hearts what we’re suffering for.

I really liked this piece, but I'd like to push back against something (if not for the sake of "engagement"). It seems to me that it's not so much transparency (like a house seen by all), but it's intent and use (just like technology) that can be spiritually harmful. To support this, I'd like to point that early (really early) first confession in the Church was a 'public' event, aka transparent.