The 19th century materialist philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach said that “Man is what he eats.”

While this statement was meant to repudiate idealism and religious thought, the 20th century Orthodox priest and scholar Fr. Alexander Schmemann noted that our German friend was expressing, “without knowing it, the most religious idea of man.”

After all, the Romans accused the early Christians of cannabalism, and not without some reason.

Schmemann begins his book For The Life of The World:

In the biblical story of creation man is presented, first of all, as a hungry being, and the whole world as his food. Second only to the direction to propagate and have dominion over the earth, according to the author of the first chapter of Genesis, is God's instruction to men to eat of the earth: "Behold I have given you every herb bearing seed . . . and every tree, which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat. . . ." Man must eat in order to live; he must take the world into his body and transform it into himself, into flesh and blood. He is indeed that which he eats, and the whole world is presented as one all-embracing banquet table for man. And this image of the banquet remains, throughout the whole Bible, the central image of life. It is the image of life at its creation and also the image of life at its end and fulfillment: ". . . that you eat and drink at my table in my Kingdom."

St. Paul warns the Christians in Corinth not to eat in an idol’s temple, that is, to not share a meal with demons.

While fasting has become a popular “technique” in health circles there is little talk in the mainstream regarding feasting, at least explicitly. This is in large part due to our mass affluence in the West. Your typical American has access to a caloric excess which would make most kings throughout history flush with envy.

And yet what has this excess brought us?

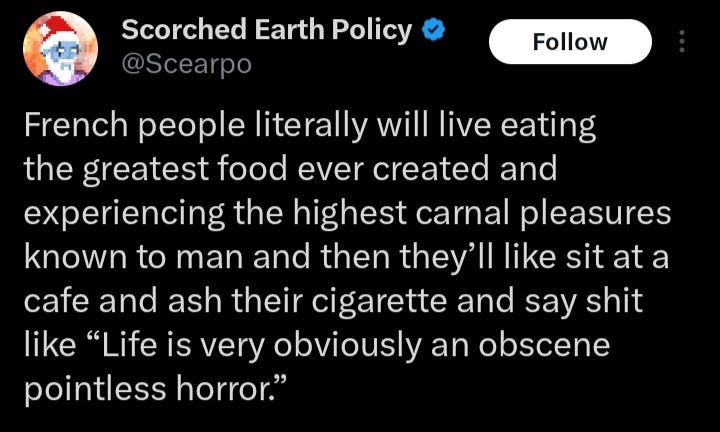

In this world, to feast continually is to cease feasting altogether; we simply enter into “an obscene pointless horror” of mere physical indulgence. We must first prepare to feast, and one way of doing this is by fasting. But to fast without the feast to come turns into self-flaggellation. We need something to move towards if our hearts aren’t to falter.

Dr. Timothy Patitsas in his book The Ethics of Beauty says that “Eros is the beginning of human moral life.” He explains that this is not eros in the sense that most westernerns use the term—to describe unrestrained sensuality or consuming selifshness—but "the love that makes us forget ourselves entirely and run towards the other without any regard for ourselves.”

For a Christian, pure eros is one directed towards Christ. Patitsas notes that:

Fasting is how we purify eros, while feasting is how we intensify it. The two only make sense together. And fasting and feasting both involve the body, showing that the spiritual life involves the total human person.

At this point you might rightly ask where the digital comes into play in all of this? Honestly, in preparation for this piece I realized that the above framework of feasting and fasting was necessary before talking more directly about what digital fasting is or could be, among other implications.

Next week we’ll continue with Pt. II, focusing directly on the digital realm, before finishing up with Pt. III, looking at calendars.

I really like this piece and where it's going. I'll eagerly be reading the rest. The idea that the digital realm is all good or all bad seems unsatisfying and doesn't answer the issues IMO.

Nice read. Twas a good lead up to the starting line.